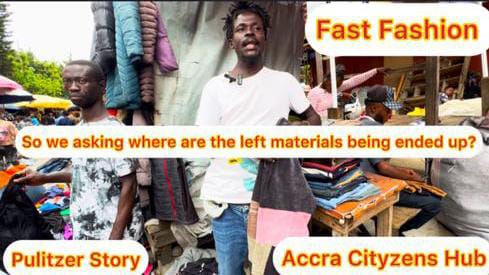

Where Does The Unused Clothes End Up: The Story Behind Kantamanto’s Unused Clothes

In the glossy world of fashion, new outfits trend and fade in a matter of days. The world’s biggest clothing brands promise affordability and style—with a new wardrobe just a click away. But behind the bright store lights and online shopping carts lies a global crisis, one that silently piles up on the streets and drains the environment in places far from the world’s fashion capitals. One of the most significant victims of this fast fashion cycle is Ghana, and at the heart of it sits the iconic Kantamanto Market in Accra—the world’s largest second-hand clothing hub called here as “Obroni Wawu.

From Fashion Capitals to Kantamanto

Every week, Ghana receives millions of discarded garments from Europe, North America, and Asia. These clothes—originally donated to charity bins or thrift stores as “gifts”—travel a long and costly route. Wholesalers purchase them, ship them to Africa, and they end up in bales stacked at Kantamanto. Many are not gently used clothes as consumers imagine. Instead, they are unsold store stock, returns, damaged items, or completely unused clothing that fast fashion companies over-produced and consumers quickly abandoned.

Each bale is a gamble. Traders buy them without knowing the contents, hoping there will be quality pieces. The risks are high but livelihoods depend on it.

The Harsh Reality: Not All Clothes Find a Home

While Kantamanto’s tailors, recyclers, and traders work tirelessly to give garments a second life, the truth is stark:

- 40% or more of clothes are unsellable

- Many arrive stained, torn, fake-branded, or too low-quality to reuse

- Massive piles accumulate daily, overwhelming the market’s capacity

What happens next paints the real picture of fast fashion’s hidden cost.

Where the Unused Clothes End Up

When the bales are opened, the true burden unfolds. Clothes that do not make it to hangers or stalls end up in:

✅ Dump sites across Accra

✅ Burning pits, adding to air pollution

✅ Deep drains, causing floods during rainy seasons

✅ Beaches, carried by wind and rainwater

✅ The ocean, where fabric fibers choke marine ecosystems

Ghana never asked to be the world’s wastebasket—but it pays the environmental price.

The Social Impact: Traders and Tailors in the Middle

In Kantamanto, thousands of traders, porters (kayayei), tailors, and upcyclers depend on second-hand clothing for survival. They are part of one of Africa’s most creative circular economies. Yet fast fashion’s waste threatens them too. Poor-quality imports leave sellers in debt and waste handlers struggling with mountains of textiles they never created. One of the most of interesting quotes from the article “What Fast Fashion Costs The World”. “I first became curious about the afterlives of our clothing last year, when I began thrifting in Johannesburg as an antidote to my pandemic malaise” read full story here Pulitzercentre.org

Still, innovation thrives:

- Local designers upcycle old clothes into new fashion

- Tailors repair and redesign pieces

- Youth-led fashion brands promote sustainable made-in-Ghana style

Despite global waste dumping, Ghanaian creativity rises.

The Hidden Cost of “Cheap” Clothing

The real price of fast fashion doesn’t show up on the price tag.

It shows up in:

- Polluted shorelines in Jamestown and Korle Lagoon

- Choked drains in Accra’s busiest markets

- Health risks from burning synthetic fabrics

- Economic loss for traders forced to discard poor-quality stock

- Cultural erosion, as traditional textiles compete with Western fashion waste

The clothing that is meant to be “reused” often becomes landfill within weeks, not years.

A Path Toward Sustainable Fashion

Solving the problem isn’t simple—but it’s possible. Progress requires:

💡 Clothing companies taking responsibility for over-production

💡 Importation policies to filter poor-quality waste clothing

💡 Investment in local textile recycling industries

💡 Supporting Ghanaian designers and tailors

💡 Global consumers choosing quality over quantity

Fast fashion’s lifecycle should not end in the gutters of Accra.

Conclusion

Kantamanto is more than a market—it’s a mirror reflecting the consequences of global waste culture. While fast fashion pushes more products with faster turnover, Ghana bears the hidden burden. Yet through creativity, resilience, and innovation, Ghanaians continue to breathe life into garments others deemed worthless.

The next time someone clicks “Add to Cart,” they should ask:

Who really pays the price?